Step into a world where ancient spirits whisper in the mist, brave knights clash with mythical beasts, and cunning animals outwit their foes. This is the rich, vibrant landscape of French folklore, a tapestry woven from centuries of diverse cultural threads. Unraveling the origins and evolution of French folklore isn't just a historical exercise; it's an exploration of the soul of a nation, revealing how stories shaped identities, morals, and dreams across generations. From the epic sagas of medieval heroes to the enchanting fairy tales that still captivate us today, these narratives offer a unique window into the heart of France.

At a Glance: What You'll Discover About French Folklore

- French folklore is a rich blend of Celtic, Roman, Germanic, and Christian influences, reflecting centuries of conquest and cultural exchange.

- It evolved from ancient oral traditions, gradually codified and transformed by medieval literature like chansons de geste and Arthurian romances.

- The printing press propelled folklore into new forms, with Rabelais's satirical giants and Perrault's classic fairy tales becoming foundational.

- 19th-century scholars diligently preserved regional tales, safeguarding unique local identities and reviving Celtic heritage.

- The stories feature an unforgettable cast: from powerful fairies and mischievous sprites to fearsome dragons and valiant saints, all serving to entertain, educate, and define.

The Deep Tapestry: Unearthing Folklore's Ancient Roots

Before France was France, its lands were home to diverse peoples, each bringing their own worldview, spirits, and stories. This ancient crucible of cultures laid the groundwork for the fascinating folklore we know today.

A Confluence of Cultures: Celtic, Roman, Germanic, Christian Influences

The bedrock of French folklore is truly multicultural. Imagine the misty, ancient forests of Gaul, where Celtic bards sang of shape-shifting gods and nature spirits like the korrigans of Brittany. Then came the Roman legions, bringing their own myths, heroes, and administrative structures, subtly layering Latin traditions over existing ones. Later, Germanic tribes, such as the Franks, swept in, introducing their sagas of loyalty and martial valor.

But perhaps the most profound influence came with the rise of Christianity. Medieval Christian tenets began to reframe older pagan beliefs, often transforming ancient deities into saints, demons, or simply magical beings. This fusion meant that a story might feature a Christian knight fighting a pagan giant, or a fairy tale might impart a distinctly Christian moral lesson. This constant cultural conversation is what gives French folklore its unique depth and complexity.

The Power of the Spoken Word: Oral Traditions Reign Supreme

For millennia, stories weren't written down; they were lived, performed, and passed from mouth to ear. Ancient oral traditions were the primary vessels for transmitting myths, legends, and customs. Imagine a medieval hearth, where a storyteller, or conteur, captivated listeners with tales of brave heroes, mischievous spirits, and moral dilemmas. These narratives served not only to entertain but also to educate, socialize, and preserve the collective memory of a community. The very act of telling and retelling allowed stories to adapt, incorporating new events, characters, and regional specificities, making them living, breathing cultural artifacts.

Medieval Echoes: From Epic Deeds to Everyday Morals

The medieval period in France was a crucible of creativity, where oral traditions began to solidify into written forms, shaping not just French literature but the broader European narrative landscape.

Chivalry and Valor: The Chansons de Geste

One of the most striking medieval developments was the chansons de geste, or "songs of heroic deeds." These epic poems, performed orally from the 10th to the 13th centuries, blended historical events with legendary embellishments, celebrating the ideals of feudal loyalty and Christian triumph. Imagine vast halls where a bard would chant the glorious feats of Charlemagne and his paladins, blurring the lines between history and myth.

The Geste du roi cycle, focusing on Charlemagne (8th-9th centuries), is a prime example, emphasizing loyalty and divine intervention. The undisputed masterpiece is the 11th-century La Chanson de Roland, which immortalizes the betrayal of Roland at Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, transforming a military skirmish into a mythic clash between Christian chivalry and Saracen might. These epics skillfully integrated older pagan elements—giants, enchanted swords—into a distinctly Christian framework, contributing significantly to the emerging French national identity by the late 12th century.

Love, Loyalty, and Magic: Arthurian Romances and Troubadour Tales

Parallel to the heroic epics, another powerful narrative stream emerged: the Arthurian romances. Chrétien de Troyes, a 12th-century poet, was instrumental in adapting Celtic lays into sophisticated chivalric tales. His works, like Perceval, or the Story of the Grail, introduced iconic figures like Merlin and Excalibur, blending Celtic motifs with Christian allegory. These romances explored themes of courtly love, adventure, and the quest for spiritual purity, deeply influencing European literature.

The same era saw the rise of the troubadours in Occitania (12th-13th centuries), poets like Guilhem IX of Aquitaine and Bernart de Ventadorn, who composed the first extensive vernacular lyric poetry. Their songs, often focused on courtly love (fin'amor), transmitted oral motifs of chivalry, betrayal, and supernatural lovers. A similar trouvère tradition blossomed in northern France, further enriching the poetic landscape and showcasing the diverse regional expressions of French folklore. Post-medieval retellings, such as the 13th-century Prose Tristan, further deepened these cycles, exploring tragic romance, prophetic doom, and intense interpersonal betrayals.

Witty Wisdom: Fabliaux, Fables, and the Roman de Renart

While epics and romances glorified nobility and heroism, other forms of folklore offered a more grounded, often satirical, view of medieval life. Fabliaux (12th-14th centuries) were short, bawdy tales that delightfully mocked the clergy and nobility, often celebrating the trickery of common folk. Think of Le Vilain qui conquist paradis par plaid (The Peasant Who Conquered Paradise by Lawsuit), where wit triumphs over status.

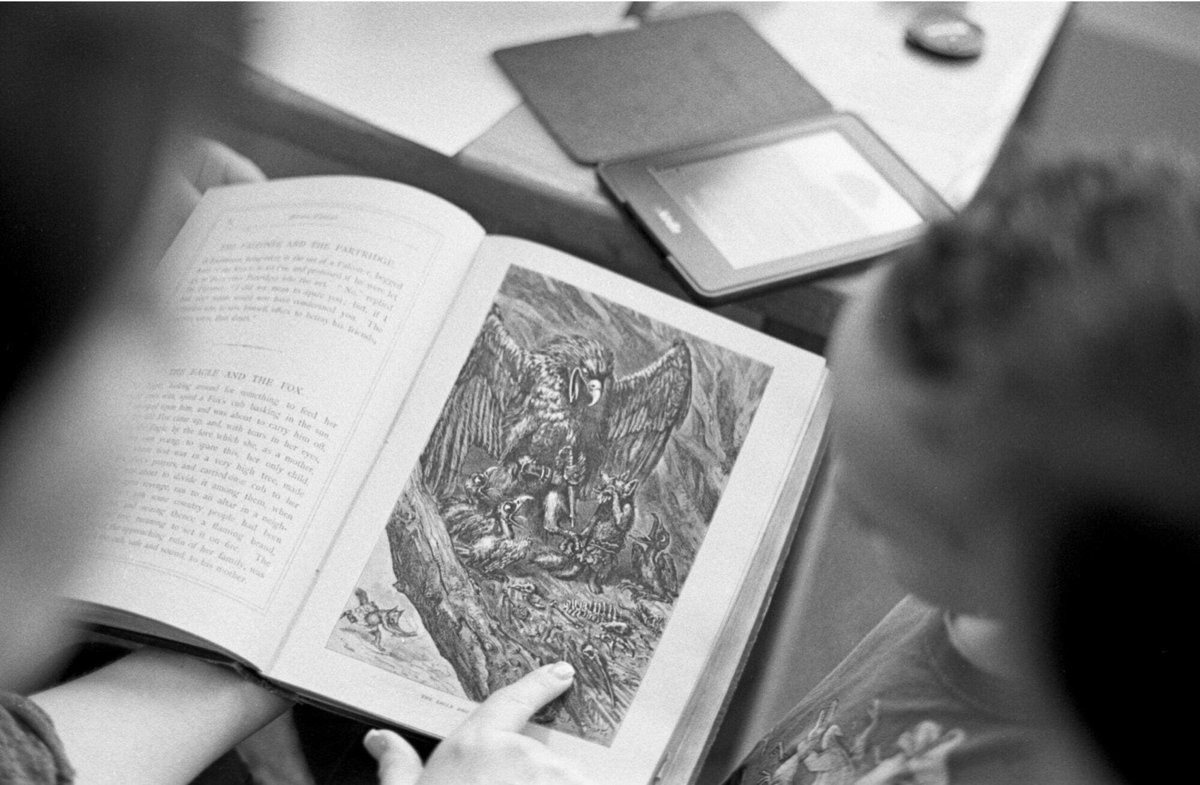

Animal fables, inspired by Aesop, also thrived. Marie de France, a 12th-century poet, adapted 102 fables in her Ysopet, using talking animals to impart moral lessons. These tales were more than simple children's stories; they were sharp social commentary. The Roman de Renart (12th-13th century), a sprawling mock epic, brilliantly parodied chivalric tales. It depicted an animal society — with Reynard the fox constantly outsmarting Ysengrin the wolf — as a satirical microcosm of human vices. These genres played a crucial role in preserving oral folk wisdom and allowed for subversive social critique.

Bridging Worlds: Folklore's Renaissance in Print

The advent of the printing press fundamentally changed how folklore was transmitted and consumed. What was once exclusively oral or manuscript-bound could now reach a wider audience, evolving in form and function.

Giants and Satire: Rabelais' Revolutionary Gargantua and Pantagruel

The 16th century saw François Rabelais (c. 1532-1564) take popular giant lore and transform it into a vehicle for profound satirical commentary. His five-book series, Gargantua and Pantagruel, published pseudonymously, introduced the colossal, excessively consuming giants who satirized medieval pedagogy, religion, and society with carnivalesque gusto.

Rabelais’ use of vernacular French democratized humanistic ideas, weaving in proverbs, riddles, and mock genealogies drawn directly from oral giant tales and chapbooks. His work was a powerful bridge between the raw energy of oral tradition and sophisticated literary critique, popularizing motifs that would resonate through French folklore for centuries.

Society's Mirror: Satirical Tales of the 16th and 17th Centuries

The spirit of satire continued to flourish in French literature. Marguerite de Navarre's Heptaméron (1542), a collection of 72 tales, offered sharp social commentary on provincial life. Later, Paul Scarron's Le Virgile travesti (1648–1653) famously parodied Virgil's Aeneid with vulgar humor, popularizing the "travesty" form where classical myths were humorously debased.

These works, while seemingly mocking the past, often preserved elements of oral folklore through contes drôlatiques (comical tales). Noël du Fail's Propos rustiques (1547–1553), for instance, captured authentic Breton oral dialogues, showcasing how writers, even when pushing boundaries, kept older traditions alive in new literary forms.

The Golden Age of Fairy Tales: From Salon to Standard

The late 17th century marked a pivotal moment, transforming raw folk narratives into refined literary fairy tales that would sweep across Europe and define the genre for generations.

Charles Perrault: Codifying Classic Narratives

Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a distinguished member of the Académie Française, played a monumental role in this shift. His 1697 collection, Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralitez, famously subtitled Les Contes de ma Mère l'Oye (Tales of Mother Goose), brought eight timeless stories to salon audiences.

Tales like "La Belle au bois dormant" (Sleeping Beauty) and "Cendrillon" (Cinderella) were drawn from diverse oral traditions but adapted by Perrault into morally instructive, often Christianized, forms. He standardized these once varied narratives, giving them a polished literary voice that resonated profoundly. Perrault’s tales were incredibly popular, influencing later collectors like the Brothers Grimm and seeing over 233 reprints between 1842 and 1913, solidifying their place in the collective imagination.

Madame d'Aulnoy: Crafting Courtly Enchantments

While Perrault laid the groundwork, Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy (1650–1705) truly refined the fairy tale for sophisticated adult audiences. Her main collection, Les Contes des fées (1697–1698), across four volumes, presented sixteen elaborate tales rich in psychological depth and reflecting the intrigues of Versailles' court.

Stories like "The White Cat" and "Finette Cendron" showcased complex plots centered on themes of power, disguise, and magic. D'Aulnoy is credited with popularizing the very term conte de fées ("fairy tale"), emphasizing the central role of fairies. Her amoral, sophisticated enchantments became widely influential in European aristocratic circles, swiftly translated into Tales of the Fairies (1707), cementing her legacy as a foundational figure in the genre.

The Guardians of Tradition: 19th-Century Revival and Regional Pride

The 19th century witnessed a passionate resurgence of interest in preserving indigenous folklore, driven by a burgeoning sense of national and regional identity.

Émile Souvestre: Preserving Breton Voices

In Brittany, a region steeped in Celtic heritage, Émile Souvestre (1806–1854) emerged as a pivotal figure. His Le Foyer breton (1844-1845), a two-volume collection, meticulously documented oral folklore directly from rural storytellers. Souvestre went beyond simply recording; he transcribed tales from Breton dialects into French, ensuring their cultural authenticity for a wider audience.

His work brought legends like "The Legend of the Ankou" (the skeletal harbinger of death) and "La Groac'h de l’Île du Lok" (a cunning water fairy) to national prominence. Souvestre's efforts were instrumental in elevating Breton folklore, sparking Romantic nationalism, inspiring regional identity movements, and revitalizing interest in France's ancient Celtic roots.

The Scholarly Quest: From Beaumont to Sébillot

Beyond individual collectors, the 18th and 19th centuries saw a growing academic and literary interest in folklore. Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont's Le Magasin des enfants (1756), for example, adapted tales like "La Belle et la Bête" (Beauty and the Beast) for moral instruction, much like Perrault before her.

Later in the 19th century, Paul Sébillot took a systematic approach. His 1880 questionnaire and subsequent monumental work, Le Folk-Lore de France (1904–1907), documented local superstitions, beliefs, and customs across various regions, bridging rigorous scholarship with the vibrant popular memory of France. His efforts were critical in safeguarding the diverse, distinct identities of French regional folklore from the homogenizing forces of modernization.

Iconic Figures and Supernatural Beings: The Pantheon of French Folklore

French folklore is populated by an unforgettable cast of characters, from the historically real to the purely fantastical, each embodying cultural values, fears, and aspirations.

Saints, Heroes, and Outlaws: Human Icons of Legend

Legends often elevate extraordinary humans to mythic status. St. Denis, the 3rd-century patron saint of France, is famously depicted carrying his severed head, a testament to divine miraculous power. St. Joan of Arc, the 15th-century peasant girl whose visions led her to rally French forces, became a powerful patriotic symbol after her martyrdom in 1431 and eventual canonization in 1920.

Outlaws, too, captured the popular imagination; figures like Louis Dominique Cartouche, an 18th-century Parisian bandit, were romanticized as French Robin Hoods. National icons such as Clovis I, the 5th-century Merovingian king whose baptism Christianized the Franks, and Vercingetorix, the Gallic chieftain who resisted Roman conquest in 52 BC, became symbols of foundational national identity and indigenous resistance, especially in the 19th century.

Fairies, Elves, and Sprites: Guardians of Nature and Mischief

The supernatural realm is teeming with ethereal beings. Fées (fairies) are central figures, often associated with nature and possessing immense power. Mélusine, immortalized in Jean d'Arras's 1393 romance, is a tragic fairy cursed to transform into a half-serpent every Saturday. Elves and lutins are mischievous household sprites, often requiring small offerings to keep them happy, with the Norman Nain Rouge ("Red Dwarf") being a distinctive regional variant.

In Brittany, the korrigans, shape-shifting fairy folk with deep Celtic roots, dwell near sacred sites, sometimes luring mortals to their doom. Beliefs in these spirits persisted well into the 19th century, evidenced by rituals like nightly milk offerings for the Iouton, reflecting a desire to maintain balance with the unseen world.

Beasts, Dragons, and Monsters: Confronting Chaos

French folklore also grapples with chaos and moral peril through its monstrous creatures. The Tarasque, a fearsome Provençal dragon, was famously tamed by Saint Martha in the 13th-century Golden Legend, a narrative that still inspires Tarascon's annual procession (recognized by UNESCO in 2005). The Gargouille, a spouting dragon near Rouen, subdued by Saint Romain in the 7th century, is said to have inspired the architectural gargoyles on cathedrals.

Werewolves (loup-garou) haunted 16th-century rural tales, leading to real-world trials and executions, such as those of Pierre Burgot (1521) and Gilles Garnier (1573). Other terrifying creatures include the basilisk (a cock-dragon hybrid with a fatal gaze) and the Vouivre (a flying serpent guarding treasures). These beasts often carry Christian allegorical weight, representing sin or untamed nature, their slaying a metaphor for spiritual or societal triumph. To dive deeper into these enchanting narratives, you might want to explore French tales yourself!

A Mosaic of Tales: Regional Flavors of France

One of the most captivating aspects of French folklore is its incredible regional diversity. The shape and character of tales shift dramatically as you move across the country, a testament to distinct historical paths, languages, and environments.

In Brittany, Celtic influences are undeniable. Here, you encounter the spectral Ankou, the skeletal harbinger of death, and the enigmatic korrigans, nocturnal dwarves dancing around dolmens, reflecting an ancient, powerful connection to the land and its pagan past. Move east to Alsace, and Germanic influences become clear, with fears of the strie (witches) echoing a different cultural lineage.

Provençal tales, rich with Mediterranean warmth and Roman history, feature local variants of the loup-garou and the renowned legend of the Tarasque. Geographic isolation fostered unique entities in specific areas—Alpine dragons in the high mountains, or coastal water lutins along the seaboard. The 19th-century preservation efforts, notably Paul Sébillot's extensive collections like Le Folk-Lore de France, were crucial in documenting these regional variants, actively safeguarding these distinct local identities against a centralizing national culture.

Beyond Narratives: Proverbs, Riddles, and Rituals

Folklore isn't just about stories; it's also embedded in everyday expressions and communal practices, guiding behavior and strengthening social bonds.

French proverbes (proverbs) are a cornerstone of this non-narrative folklore, conveying timeless wisdom in concise phrases, such as "Petit à petit, l'oiseau fait son nid" ("Little by little, the bird makes its nest"). Énigmes (riddles) offer playful intellectual challenges, engaging communities in shared wit.

Festive rituals are another vital component, blending seasonal cycles with vibrant communal expression. Mi-carême, for example, marks mid-Lent with masked parades, offering a moment of joyful release before Easter. The Feu de la Saint-Jean (Saint John's Fire) on June 23-24 involves bonfires, stemming from ancient pagan solstice rites, meant to ward off evil and ensure bountiful harvests. These diverse elements — whether narrative, linguistic, or ritualistic — collectively transmit cultural norms, provide moral education, and reinforce group cohesion, ensuring the continuity of French identity and wisdom through the ages.

What Makes French Folklore Enduring?

The journey through the origins and evolution of French folklore reveals a constant interplay between the ancient and the modern, the local and the universal. It’s a tradition that has absorbed countless influences, adapted through new technologies, and served myriad purposes, from moral instruction to social satire, from national identity building to pure entertainment.

French folklore endures because it speaks to universal human experiences: courage in the face of adversity, the triumph of good over evil, the mysteries of nature, and the complexities of the human heart. It offers a looking glass into the historical mind of France, yet its core themes remain profoundly relevant. These tales, proverbs, and rituals continue to shape cultural understanding, inspire new artistic creations, and remind us of the power of storytelling to connect us across time and space. The stories might change their clothes, but their heart beats on, inviting us to listen and learn.